Our societies are largely anti–life span and prodeath. When we upgrade to Human 2.0, we may look back on the present as our savage history.[1]

Consider the following diary entries from Mary Vial Holyoke, a New England woman born in 1737:

Jan. 8, 1764. First wore my new Cloth riding hood.

9. My Daughter Polly first confined with the quinsy. Took a vomit.

10. Nabby Cloutman watch’d with her.

11. Very ill. Molly Molton watched.

12. Zilla Symonds watched.

13. My Dear Polly Died. Sister Prissy came.

14. Buried.

17. Small Pox began to spread at Boston.

19. Mrs. Fitch came from Boston for fear of small pox.

21. Town meeting for guarding the town from small pox.

22. Dr. Lloyd Came from Boston to see Stephen Higginson.

24. A violent snow storm. College burnt.

25. Mr. [John] Appleton moved to the pest house with the small pox which proved to be Chicken Pox.

27. First heard of their inoculating at Boston.

29. Dr. Gardiner Came from Boston. Mrs. Vans brought to bed.

31. Mr. Oliver’s child taken with Convulsions.[2]

Life was precarious for Holyoke and her community. It would take more than two centuries after these diary entries to eradicate smallpox, which wasted away its victims and left them disfigured if not dead.[3] But what is most poignant in Holyoke’s record of daily life is her matter-of-fact mention of her daughter’s death.[4] Despite that Holyoke’s husband was an esteemed physician, for five straight years her children died. Only three of twelve matured into adulthood.[5] At the turn of the nineteenth century, between one-third and one-half of the world’s children died before they turned five years old.[6]

Child death was so common in nineteenth-century America that parents “used the loss of infants as an occasion for demonstrating their willingness to submit to the will of God and found comfort in the belief that their children had gone to join Him in heaven.”[7] Mourners turned to child elegies, an enormously popular subgenre of poetry, for comfort.[8] Bestselling writer Lydia Sigourney was famous for her elegies; she encouraged grieving readers to see death “as the consummation of our highest hope, the end for which we were born, the summons to arise, and take upon us the nature of angels.”[9] Years later, she watched her nineteen-year-old son die from pulmonary disease. She wondered, when strolling his former walking paths, whether talking to her dead son was wrong.[10]

American writers adapted to premature death by recasting the dying as God's chosen ones. Child death scenes were so ubiquitous in 1800s fiction that scholars termed the dying youngster of such works the “special child”—a loving, angelic, morally courageous little one too good for this earth and only on it briefly to be an exemplar of unwavering Christian faith.[11]

⁜ ⁜ ⁜

Infant and youth mortality rates have plummeted in all countries. Global infant mortality and youth mortality today are 2.9% and 4.3%, respectively.[12] These numbers are feats unimaginable to our distant ancestors. According to Our World in Data, “From 10,000 BCE to 1700 the world population grew by only 0.04% annually.”[13] In other words, “Birth rates were high, but population growth was close to zero.”[14]

We have nearly solved the catastrophe of mortality for the young. Why not dedicate our science and technology to unraveling its analog: aging. Nature afflicts those past prime childbearing age with an array of debilitating diseases to root them out of the gene pool. There will be hardship enough in life, can we alleviate unnecessary suffering?

In her 1838 book Letters to Mothers, Sigourney asked,

Who teaches like Death? Who like him reveals character? and unveils motives which had lain for many years, in a locked casket? and strips the illusion from the things which men covet? and makes us feel our own pitiable weakness, in not being able to soften the last pang for those we love?[15]

Sigourney was not against optimization—Christian piety was her measure for optimization. She wrote at a time when there was far less medical expertise to save or aid the dying. When there is no other recourse but submission, we craft narratives that make the unbearable tolerable, even desirable.

Culture is an attempt to make meaning of the cards one has been dealt. But when we can deal new cards throughout the game, we can change our culture to reflect our current or potential reality.

⁜ ⁜ ⁜

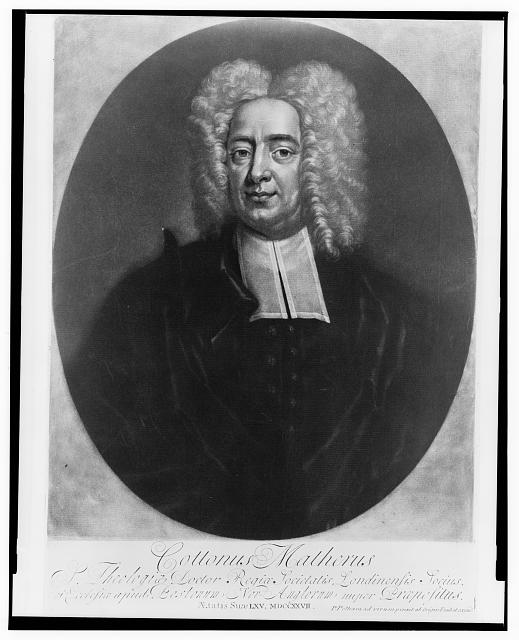

Four decades before smallpox curled its vicious fingers around Holyoke’s world, another Bostonian watched the virus unleash terror in the city. Puritan minister Cotton Mather agonized over whether to inoculate his son.[16] Mather learned of inoculation through Onesimus, an African man whom he enslaved, who informed Mather of the procedure commonly used in his homeland for protection against smallpox.[17] After fact-checking with other sources, the clergyman became an inoculation bull.[18] Variolations could include blowing smallpox scabs up the nose or exposing a small cut on the skin to smallpox scabs; both induced a muted case of smallpox that led to immunity and a higher survival rate than natural infection.[19]

Backed with promising data and an early version of a clinical trial, Mather promoted inoculation publicly at great personal risk.[20] His community turned against him and a bomb was flown at his window with the note: “Cotton Mather, you dog, dam [sic] you! I’ll inoculate you with this; with a pox to you.”[21] Mather credited the public's fury to the Devil:

The Destroyer, being enraged at the Proposal of any Thing, that may rescue the Lives of our poor People from him, has taken a strange Possession of the People on this Occasion. They rave, they rail, they blaspheme.[22]

Mather gives a clear ultimatum: If you are not in favor of optimizing for longer, healthier human lives, then you are prodeath. Full stop.

Interventions that ward off death may appear strange, but none are as strange as our resignation to die. Mather’s courage might have saved his son’s life. Samuel was the only child, out of over a dozen, who outlived his father and lived to nearly eighty years old.[23]

Human optimization is not just about making the average person healthier but realizing that the average “healthy” person isn’t that healthy at all. By enhancing the quality and quantity of our lives, we can correct the errors we unknowingly have about a biological system as complex as the human body. We can raise the bar for what it means to be healthy and move closer to it. We can spare our children, and the future children we may never meet, the agony accepted as rent to be paid for being alive.

We do not have to suffer the premature deaths of our loved ones to relearn the value of human life. Neither do we need a grim reaper at our shoulder to appreciate and embrace existence. We might revise Sigourney’s question to instead ask: Who teaches like Life?

Notes

[1] When I use the term “life span,” I imply health span even though they are distinct concepts in the medical literature. The most desirable life for me is both long and healthy.

[2] Margo Culley, ed., A Day at a Time: The Diary Literature of American Women from 1764 to the Present (New York: Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 1985), 29; Rev. Edward Holyoke et al., The Holyoke Diaries, 1709–1856 (Salem, MA: Essex Institute, 1911), 60–61, https://www.noblenet.org/salem/reference/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Holyoke-Diaries-The-1709-1856-Mrs.-Mary-Vial-Holyoke-of-Salem-1760-1800.pdf.

[3] Elizabeth A. Fenn, Pox Americana: The Great Smallpox Epidemic of 1775–82 (New York: Hill and Wang, 2001), 3–6. According to the CDC, “there are now only two locations that officially store and handle variola virus [smallpox] under WHO supervision: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia, and the State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology (VECTOR Institute) in Koltsovo, Russia.” “History of Smallpox,” Smallpox, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, last modified February 20, 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/history/history.html.

[4] Mary’s list-like diary entries typify how Americans in this period recorded their lives. Culley, A Day at a Time, 3–4.

[5] Culley, A Day at a Time, 29.

[6] Max Roser, Hannah Ritchie, and Bernadeta Dadonaite, “Child and Infant Mortality,” Our World in Data, last modified November 2019, https://ourworldindata.org/child-mortality#:~:text=The%20global%20average%20child%20mortality,on%20a%20much%20higher%20level.

[7] Sylvia D. Hoffert, “‘A Very Peculiar Sorrow’: Attitudes Toward Infant Death in the Urban Northeast, 1800–1860,” American Quarterly 39, no. 4 (Winter 1987): 601–602, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2713127?seq=1.

[8] Hannah Brooks-Motl, “Elizabeth Drew Barstow Stoddard: ‘One Morn I Left Him in His Bed,’” Poetry Foundation, February 16, 2011, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69641/elizabeth-drew-barrow-stoddard-one-morn-i-left-him-in-his-bed.

[9] Timothy H. Scherman, “Sigourney, Lydia Huntley,” in The Oxford Companion to Women’s Writing in the United States, ed. Cathy N. Davidson et al. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), Oxford Reference; Lydia H. Sigourney, “Letter XXII. Death.,” in Letters to Mothers (Hartford, CT: Hudson and Skinner, 1838), 233, Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture, Stephen Railton and University of Virginia, accessed July 31, 2022, http://utc.iath.virginia.edu/sentimnt/sneslhsa11t.html.

[10] L. H. Sigourney, “Sickness and Decline,” chap. 7 in The Faded Hope (New York: Robert Carter, 1853), 210–245, https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Faded_Hope/Uf5ZAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

[11] Nina Baym, Woman’s Fiction: A Guide to Novels by and about Women in America, 1820–70, 2nd ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993), 15–16.

[12] Max Roser, “Mortality in the Past – Around Half Died as Children,” Our World in Data, June 11, 2019, https://ourworldindata.org/child-mortality-in-the-past.

[13] Roser, “Mortality in the Past.”

[14] Roser, “Mortality in the Past.”

[15] Sigourney, “Letter XXII. Death.,” 236.

[16] T. E. C. Jr., “Cotton Mather Anguishes over the Consequences of His Son’s Inoculation against Smallpox,” Pediatrics 53, no. 5 (May 1974): 756, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.53.5.756.

[17] Matthew Niederhuber, “The Fight over Inoculation during the 1721 Boston Smallpox Epidemic,” Science in the News, Harvard University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, December 31, 2014, https://sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/special-edition-on-infectious-disease/2014/the-fight-over-inoculation-during-the-1721-boston-smallpox-epidemic/.

[18] Before the West learned of smallpox inoculation, it was deployed in Africa, China, India, and Turkey. Niederhuber, “Fight over Inoculation.”

[19] Niederhuber, “Fight over Inoculation.”

[20] Niederhuber, “Fight over Inoculation.”

[21] Niederhuber, “Fight over Inoculation.”

[22] T. E. C. Jr., “Cotton Mather Anguishes,” 756.

[23] John Langdon Sibley, Biographical Sketches of Graduates of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, vol. 3, 1678–1689 (Cambridge, MA: Charles William Sever, 1885), 41, Internet Archive, accessed September 10, 2022, https://archive.org/details/sibleysharvardgr03sibl/page/40/mode/2up.