Technological conservativism is a hangover from the ancient world. Instead of punishing explorers, embolden them to transcend the known world.

In the first volume of her two-part exegesis The Woman’s Bible (1895, 1898), Elizabeth Cady Stanton challenged the consensus that Eve of the Genesis creation story was a fallen woman. Stanton wrote that Eve’s tempter, the serpent,

had a profound knowledge of human nature, and saw at a glance the high character of the person he met by chance in his walks in the garden. He did not try to tempt her from the path of duty by brilliant jewels, rich dresses, worldly luxuries or pleasures, but with the promise of knowledge, with the wisdom of the Gods. Like Socrates or Plato, his powers of conversation and asking puzzling questions, were no doubt marvellous [sic], and he roused in the woman that intense thirst for knowledge, that the simple pleasures of picking flowers and talking with Adam did not satisfy.[1]

Though God forbids Adam and Eve from eating fruit from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, the serpent assures her that disobedience leads not to death but rather: “Your eyes shall be opened, and ye shall be as gods, knowing good and evil.”[2] Eager to upgrade her consciousness and merge with the divine, Eve is the first transhumanist in Christian history.

Eve is among a coterie of rebels in Western mythology who push the boundaries of human cognition and are punished for it. A familiar cast of characters populates our cultural myths—Pandora, Prometheus, Icarus, the builders of the Tower of Babel, the wives of Blue Beard—so that pagan, Christian, and secular culture converge to whisper the same warning: Seek no further.

Thousands of years later, the ancient impulse to limit human potential remains. We still appeal to a higher authority that will humble truth-seekers. That authority is sometimes God, but in secular contexts it is “common sense” and “tradition.” These concepts do the work of olden deities who would periodically knock the ambitious back down to an acceptable level of development.

⁜ ⁜ ⁜

We aren’t meant to live that long.

We’re not supposed to live forever.

These are the most common arguments against life extension, and not very convincing ones at that. Both assertions wish to enforce certainty and ignorance simultaneously. What’s evident is that we aren’t meant to live much longer than we already do, but why that is, no one can say. What these claims do not account for are the massive changes in life expectancy throughout history.[3]

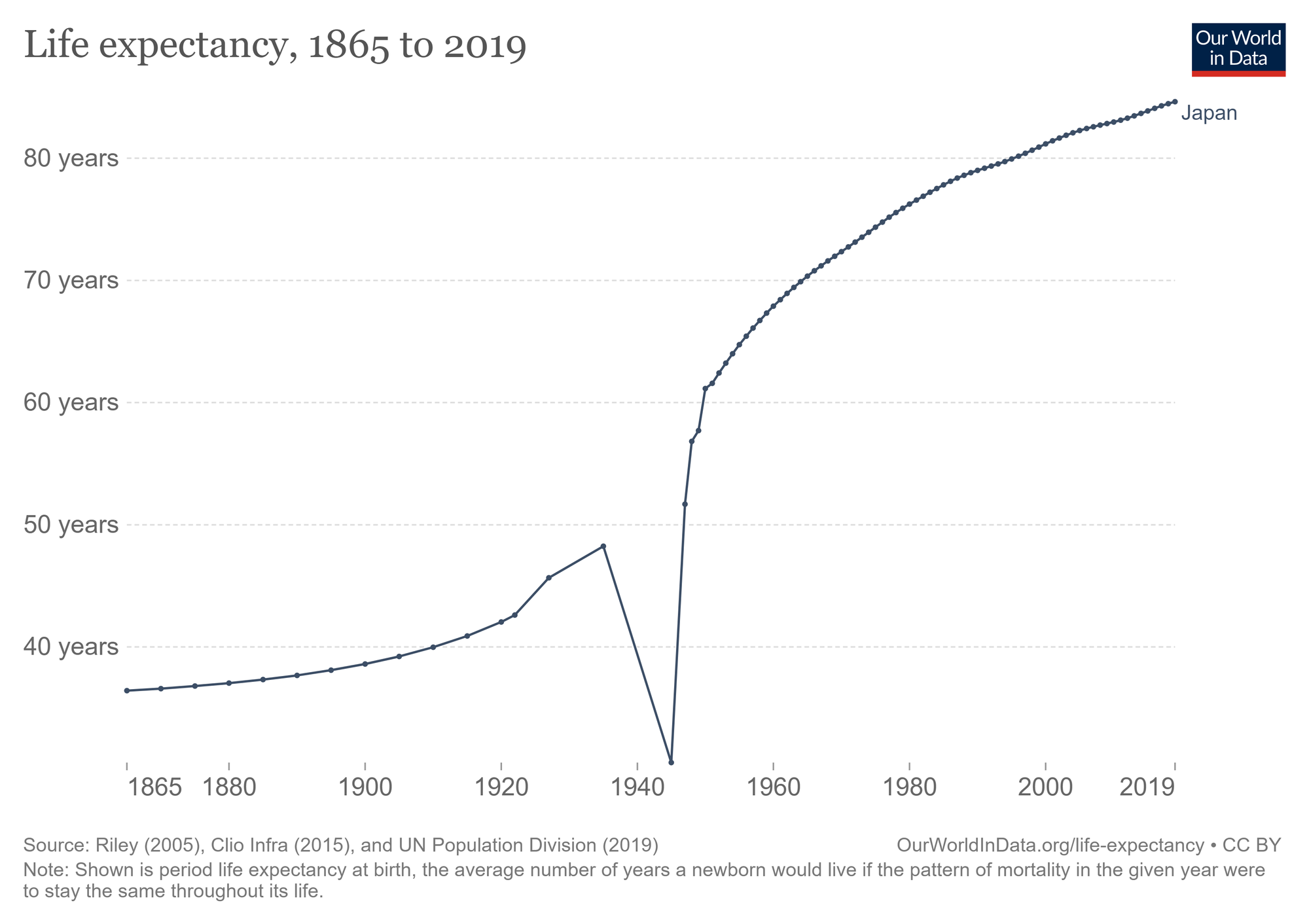

In the early 1800s, there was not a country on Earth with a life expectancy over forty years.[4] The implementation of new knowledge and technologies began to change this.[5] For someone born in Japan in 1880, the life expectancy was 37 years; in 1950, it was 61.2; in 2000, it was 81.2; in 2019, it was 84.6.[6]

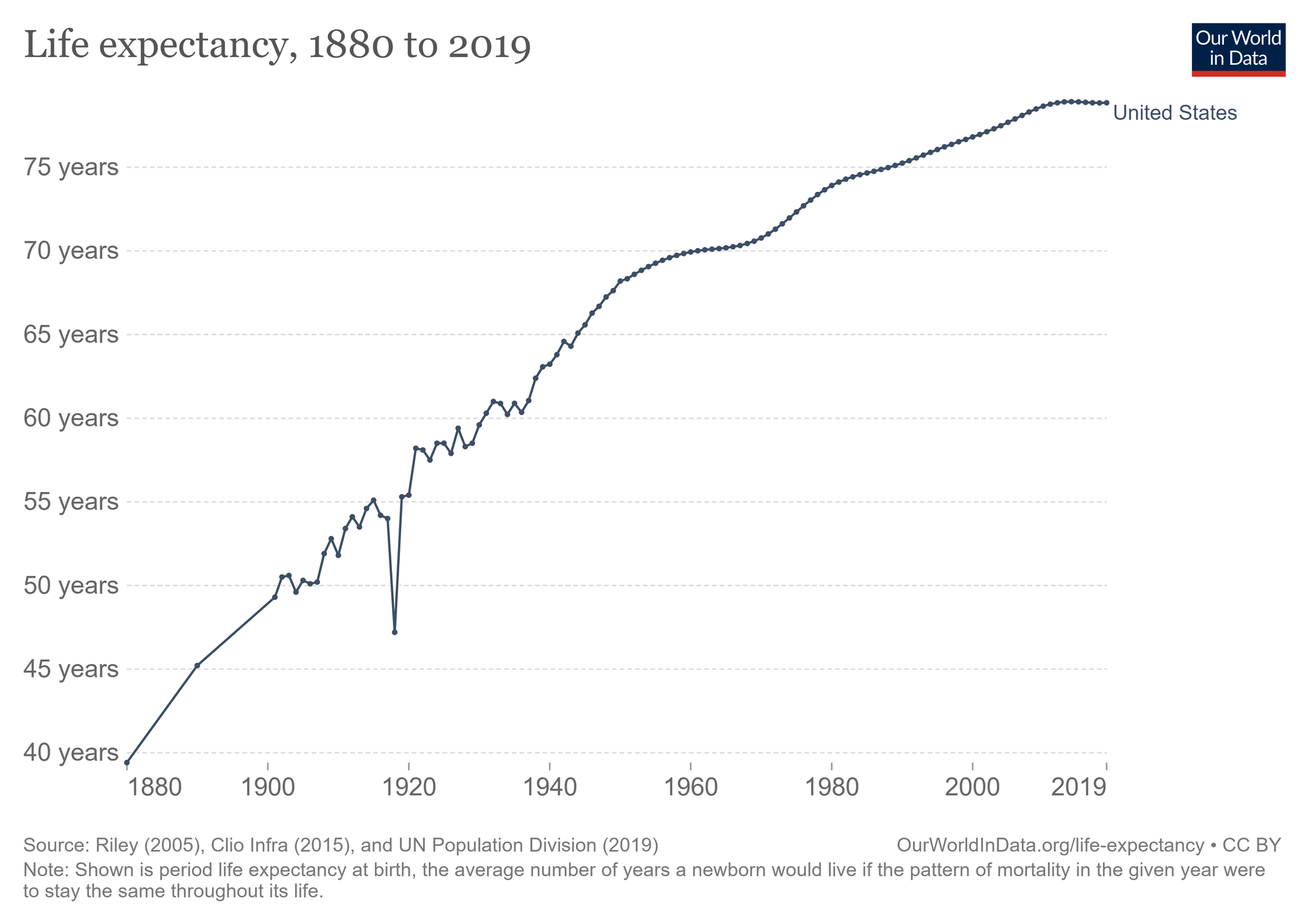

For a person born in the United States those same years, the life expectancy was 39.4, 68.2, 76.8, and 78.9 years, respectively.[7]

If life expectancy has changed across centuries, how long are humans supposed to live? If relying on the data above, should our interlocutor’s ceiling for human age be based on the numbers found in Japan, the US, or somewhere else? If there is a limit, it’s not clear we have reached it yet. Some researchers suggest the cutoff may be between 120 and 150 years, well beyond the 79–100-year range that 69 percent of surveyed Americans reported as their “ideal life span.”[8]

Desiring or designing longer, healthier lives isn’t just about continuing to enjoy our material comforts. The pursuit of longevity signals that we have a purpose motivating us and wish to see that mission through. That life can be good enough that people do not want to die is a sign of enormous human progress.[9]

We aren’t meant to . . . we’re not supposed to . . . we can’t . . . are templates to discredit initiatives that run so counter to the status quo they appear ludicrous to most people. However, when a large enough audience enjoys the benefits of an innovation, that once-bizarre proposal is embraced and becomes convention. Technology is a correction to the limits of human thinking.

We aren’t meant to fly.

Correction: hot air balloons, airplanes, helicopters, rockets, jetpacks.

We aren’t meant to see in the dark.

Correction: bonfires, torches, fireworks, candles, oil lamps, gaslight, electric light.

We can’t predict the future.

Correction: weather forecasts, pregnancy tests, prenatal testing.

Resistance to new ideas might be permissible if it effectively separated the wheat from the chaff. But pushback often goes hand in hand with protecting sterile incumbents, favoring incremental over vertical progress, and tarnishing the reputations of pioneers.[10] Underappreciated in this cruel ritual is how assassinating the character of a single innovator prevents future founders from making their ideas public. Fearful of pitchfork-wielding traditionalists, groundbreakers will struggle to bring their idea into the light or extinguish it themselves.

One wonders if we might have already cured debilitating diseases, accelerated environmental recovery, and resolved other major challenges if culture was more welcoming of innovation.

Archaic myths can no longer dictate human development. Those stories were composed and circulated at a time when it was especially dangerous to question authority. Individuals could not survive without a community and that community compelled each member to perform a predetermined role to maintain itself. Seekers who prioritized their own personal quest over the collective that depended on them could spell doom for themselves and those they left behind—especially if seekers were high-value contributors. Angry deities (or cultural deities we call norms) proved an effective strategy for capturing the labor of individuals in a culture that underserved them. When guilt, shame, and anxiety are invoked, we need to ask who benefits from the emotional torment of the few (or the many).[11]

Increasing abundance estranges us from the zero-sum world of our ancestors—the one that pitted individuals against collectives—a world in which the concept of the individual, as we know it, did not even exist. Moderns live in a different world, one where disobedience can be worthy, admirable, and in the best interest of the collective.

Society often uses the sacred in service of technological conservatism.[12] But the dividing line for progress is not between the sacred and the secular. It is between the customary and the transcendent. Since our societies have changed, perhaps our gods are also due for an upgrade.

⁜ ⁜ ⁜

Those accustomed to inheriting technological miracles without having built them need to hold on to a sense of wonder for what is possible. It’s not too late to reenchant ourselves to how technology has on the whole made life much easier, safer, equal, free, and fascinating.

Our tools have created new challenges, too, and we can feel motivated to rise to the occasion to solve them. Let’s bet on the potential and proven track record of human creativity rather than its limits. We need a new ethic for the future that encourages and cultivates progress-loving and -creating folks who rebel against complacency and jadedness.

Each of us has already exceeded the limits imposed by someone else’s god or tradition. Some believers consider the internet an expression or tool of the Antichrist—some have even proselytized this conviction online.[13] Radical as that may seem to many of the world’s five billion internet users who see the internet as the library of humanity, these doomsayers have a pulse on what technology is: the eating of forbidden fruits.[14]

In a modern retelling of the myth, we might say that Eve was trying to get to the internet. Perhaps the internet is the closest thing we have to the mind of God.

Notes

[1] Elizabeth Cady Stanton, The Woman’s Bible, Part 1: Comments on Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy (New York: European Publishing, 1895), 24–25, https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Woman_s_Bible/g3kEAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA24&printsec=frontcover.

[2] Gen. 3:5 (King James Bible).

[3] Life expectancy is “the number of years a person can expect to live. By definition, life expectancy is based on an estimate of the average age that members of a particular population group will be when they die.” Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, “‘Life Expectancy’ – What Does This Actually Mean?,” Our World in Data, August 28, 2017, https://ourworldindata.org/life-expectancy-how-is-it-calculated-and-how-should-it-be-interpreted.

[4] Max Roser, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, and Hannah Ritchie, “Life Expectancy,” Our World in Data, last modified October 2019, https://ourworldindata.org/life-expectancy#twice-as-long-life-expectancy-around-the-world.

[5] David Cutler, Angus Deaton, and Adriana Lleras-Muney, “The Determinants of Mortality,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 20, no. 3 (Summer 2006): 116, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.20.3.97.

[6] “Life Expectancy, 1865 to 2019,” Our World in Data, accessed February 16, 2022, https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/life-expectancy?tab=chart&country=~JPN.

[7] “Life Expectancy, 1880 to 2019,” Our World in Data, accessed February 16, 2022, https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/life-expectancy?tab=chart&country=~USA.

[8] Michael Eisenstein, “Does the Human Lifespan Have a Limit?,” Nature, January 19, 2022, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-00070-1; Timothy V. Pyrkov et al., “Longitudinal Analysis of Blood Markers Reveals Progressive Loss of Resilience and Predicts Human Lifespan Limit,” Nature Communications 12, no. 2765 (May 2021), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23014-1; “Living to 120 and Beyond: Americans’ Views on Aging, Medical Advances and Radical Life Extension,” Pew Research Center, August 6, 2013, https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2013/08/06/living-to-120-and-beyond-americans-views-on-aging-medical-advances-and-radical-life-extension/.

[9] To learn about how entrepreneurs and researchers are advancing life extension, see Laura Deming, investor and founder of Longevity Fund, at https://www.ldeming.com/ and https://www.longevity.vc/; Celine Halioua, founder of Loyal, a startup dedicated to life extension for dogs, at https://www.celinehh.com/about and https://loyalfordogs.com/; and David A. Sinclair, genetics professor and Sinclair lab founder at Harvard University, at https://sinclair.hms.harvard.edu/. Methuselah Foundation is just one of many organizations supporting antiaging projects, see https://www.mfoundation.org/.

[10] “Horizontal or extensive progress means copying things that work. . . . Vertical or intensive progress means doing new things.” Peter Thiel, Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future (New York: Currency, 2014), 6.

[11] For a dive into guilt, shame, and anxiety as early human survival strategies, see Peter R. Breggin, Guilt, Shame, and Anxiety: Understanding and Overcoming Negative Emotions (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2014).

[12] Michael Lipka, “The Religious Divide on Views of Technologies That Would ‘Enhance’ Human Beings,” Pew Research Center, July 29, 2016, pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/07/29/the-religious-divide-on-views-of-technologies-that-would-enhance-human-beings/.

[13] Anastasia Clark and Chris Bell, “Smartphone Users Warned to Be Careful of the Antichrist,” BBC News, January 8, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-46794556; D. W. Pasulka, American Cosmic: UFOs, Religion, Technology (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 3.

[14] The number of internet users is 5.03 billion people as of July 2022. “Digital Around the World,” DataReportal, accessed September 7, 2022, https://datareportal.com/global-digital-overview#:~:text=Internet%20use%20around%20the%20world,500%2C000%20new%20users%20each%20day.